I Get It; I Hear You: Vanessa Cuti’s ‘Our Children’ - BASS Review 2021

|

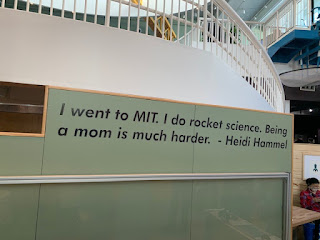

| On the wall at Explora Kids Museum, Albuquerque |

I read this story for the second time, attempting to annotate, as I followed my kids around Explora, a children’s museum in Albuquerque, NM. Despite the overstimulation everywhere, children’s museums are not typically places where I fantasize about abandoning my children. I am usually in awe of them in places like this, watching them think in ways I’d never considered, being little scientists. And yet I get it, Vanessa Cuti, and your unnamed protagonist. I tried to write this analysis many times in our domestic settings, as we moved from Albuquerque to Flagstaff, and my copy of BASS 2021 just got shifted around the houses, ever optimistic, ever accommodating toy cars and science experiments and felt-tipped pens, the demands on my attention too great to finish this piece. I didn’t want anything as cold as a glacier, but I was craving a clear expanse.

All the women and children are unnamed in this story. I immediately noticed the lack of identities of the children: it feels harsh, unloving, coming from a mother (exactly what it seems Cuti is going for), to not even identify her own children in the group, to treat them as an unpleasant mass. I didn’t notice the mothers in the story were also unnamed until about ten minutes ago. That feels appropriate, accurate.

I’m reading Jenny Odell’s ‘How to Do Nothing’ at the moment, and this morning as I was doing my scrolling of Instagram, reading the faintly funny and very samey parenting realism posts that I should really unfollow, I was reminded of the Mother of the Year award in Oakland that Odell talks of. It is awarded to a woman in the community who "symbolize[s] the finest traditions of 'motherhood’”. The criteria for this includes being an exemplary role model who has improved the quality of life for the people of Oakland. I thought of Cuti’s unnamed protagonist and how much she did not sign up for the expectation of nurture, sacrifice and altruism that comes with being a mother, that the Mother of the Year award seeks to exemplify as “doing mothering the best”. She just simply had some kids, just like people have always been doing. Generic life move, as she lays out for us in the introductory paragraph. All the characters are interchangeable. No-one told her that doing this would put her forward for judgement against this fantasy benchmark of “mother”.

I am reminded too of a conversation I had with a friend, who was writing a story about a child abandoned by her mother and who couldn’t write the mother as anything but a two-dimensional villain, because, “How could any mother abandon their child?” It is an interesting question, which Cuti explores here. This refrain is ubiquitous now, but still nothing has changed, and so I have to ask: why are we not demanding this of the fathers? The protagonist of this story is a flawed mother, feeling the guilt and weight of judgement against her (and exacting it on other mothers, all the same, with her judgements of the video games her step-kids play, and the messy car of their mother), and yet the father also abandons the kids, goes with her on a whim, and doesn’t even return at the end. If we read this as a straightforward story of something that happened in this world, then it is the mother that returns to look after the children and take care of their needs, hurrying to get there before they even wake up so they don’t even know she was gone. The father has no such concerns, is probably still asleep. Where is the judgement on him? I think that is a question Cuti is asking here, pointing to this double standard that we all recognize but fail to do much about.

This story is described by the BASS editors as magical realism, and yet the first time I read it I didn’t at all get any magical realism vibes, or any sense that this wasn’t just a straightforward story of a mother reaching some kind of breaking point and abandoning her kids for the night. It is, of course, an appalling thing to do, and not something (most) parents would ever really entertain, especially given the context (very young children, cabin in the woods)—in that respect, it is fantasy, but felt very much in the realm of possibility. After all, family abandonment is not completely unheard of. And this woman is clearly on the brink of breakdown from the pressures of being a mother, and the complications and restraints on her life that come with navigating messy stepfamilies.

In fact, in terms of magical realism, the biggest deviation from reality for me in this story was the incongruence between the ages of the children and their behavior. They are aged five to seven. The major and most obvious one is them all falling asleep of their own accord whilst watching TV together, before they’d even eaten dinner, scrunched up on sofas and armchairs, and then remaining asleep all night. I have a six year old daughter, and this is completely unimaginable to me. Also, they seem a bit young for the all-day-long video games and the swearing. Perhaps that is just judgement on my part; inducing that judgment of parents in readers seems a clever way of having us marinade in that theme. But the children do seem more like teenagers to me, particularly in their attitude towards the mother, with their mocking and sullenness. I wonder if this is intended to make us think that the mother is being paranoid, attributing malice and intent where there is none, such as when she assumes they are pointing the game controllers at her back when she leaves the room, or laughing at her polite non-swearing. Plenty of people incorrectly attribute meanness and manipulation to the behavior of young children.

From the outset, the protagonist is distant and detached from her life and her environment. She describes it clinically, with no explicit feeling, letting us know exactly how unhappy she is with the language she chooses and the things she draws attention to: the zombified listing of kid paraphernalia, the sensory overload of that. She already has my sympathy, in her retelling of how her ex-husband used to treat her, his ways of calling her fat and knocking her down. Her disappointment and disenchantment with her life is palpable throughout, and echoed in the imagining of her children growing up in the cabin alone.

I am confident that we are supposed to read the imaginings of the children growing up in the cabin as exactly that: imaginings. She extrapolates from reality, as she has been doing throughout the story—imagining judgement from other mothers and society at large, imagining an alternative life where she didn’t have children or where she stayed with her first husband, imagining what the ex-wife thinks about her, what her life is like. That is all that is happening here. It’s funny, because at first the imagining future of the kids looks very much like the ideal for a lot of mothers, at least in the hippie circles I run in: a homesteader’s dream, where the kids spend way more than the target thousand hours a year outside, untainted by technology and capitalism, connected to the earth and to nature, living simply and sustainably. This seems like pure fantasy for any mother, and is perhaps the culmination of her guilt as being such an inferior mother (in her eyes), that they will thrive and live their best lives without her, that she will do the best for them by staying away.

Then the fantasy sours. The children learn of the disappointments of life that the protagonist already feels so deeply, of the harsh realities of life, in the episode with the killing of the doe. They start out by killing it for food, which is celebrated as a self-sufficiency; then reality sets in, and they realize they cannot get it back to the house because it is too heavy. Then they worry that they do not have the skills to prepare it safely and hygienically, and that they’d better not eat it after all because it might make them sick (this is, of course, a concern more typical of mothers than of children) and so they abandon their doe-eating plans, and the doe itself. This leads to sadness and guilt that they needlessly killed something. It’s an extreme example, but works well as an analogy for the missteps of parenting, and perhaps just adult life in general: you take big steps towards something, creating irreparable change, and then realize it’s bigger than you thought, and so you abandon the goal, leaving you only with guilt and sadness and sometimes a sense of mourning for life before.

And so this flawed mother goes back to the children, to save them from all this, choosing her sacrifice this time. Ultimately, even though she doesn’t ever name her children, she does take ownership of them, and responsibility for them. She acknowledges this, and points out that this responsibility is shared across three other adults, in the titling of the story. They are our children. She is not alone.

*

Karen Carlson gets into the "show, don't tell" aspects of this story at A Just Recompense. Read it here.

Wow, maybe it takes a mom to really get this story, great comments! I'm particularly impressed that you noticed the kids don't have names. That's something I usually pay attention to, naming is important, but it went right by me here; so glad you pointed it out to me. And the title, that, too, never occurred to me. You're really good at this!

ReplyDelete